Supervised Learning

Setup

Let us formalize the supervised machine learning setup. Our training data comes in pairs of inputs $(x,y)$, where $x∈R_d$ is the input instance and y its label. The entire training data is denoted as $D={(x_1,y_1),…,(x_n,y_n)}⊆R^d×C$ where:

$R^d$ is the d-dimensional feature space $x_i$ is the input vector of the ith sample $y_i$ is the label of the ith sample $C$ is the label space The data points $(x_i,y_i)$ are drawn from some (unknown) distribution $P(X,Y)$. Ultimately we would like to learn a function h such that for a new pair $(x,y)∼P$, we have $h(x)=y$ with high probability (or $h(x)≈y$). We will get to this later. For now let us go through some examples of $X$ and $Y$.

No Free Lunch

Before we can find a function h, we must specify what type of function it is that we are looking for. It could be an artificial neural network, a decision tree or many other types of classifiers. We call the set of possible functions the hypothesis class. By specifying the hypothesis class, we are encoding important assumptions about the type of problem we are trying to learn. The No Free Lunch Theorem states that every successful ML algorithm must make assumptions. This also means that there is no single ML algorithm that works for every setting.

Summary of Introduction

We train our classifier by minimizing the training loss: Learning: \(h^∗(⋅)=argmin_{h(⋅)∈H_1}\frac{1}{|D_{TR}|}∑_{(x,y)∈D_{TR}}ℓ(x,y|h(⋅))\), where $H$ is the hypothetical class (i.e., the set of all possible classifiers $h(⋅)$). In other words, we are trying to find a hypothesis h which would have performed well on the past/known data.

We evaluate our classifier on the testing loss: Evaluation: \(ϵ_{TE}=\frac{1}{|D_{TE}|}∑_{(x,y)∈D_{TE}}ℓ(x,y|h^∗(⋅))\). If the samples are drawn i.i.d. from the same distribution $P$, then the testing loss is an unbiased estimator of the true generalization loss: Generalization: \(ϵ=E_{(x,y)}\sim P[ℓ(x,y|h^∗(⋅))]\).

Note that, this is the form of corssentrophy $H[P(y\lvert h^*(x)), P(y\rvert x)]$.

No free lunch. Every ML algorithm has to make assumptions on which hypothesis class H should you choose? This choice depends on the data, and encodes your assumptions about the data set/distribution P. Clearly, there’s no one perfect $H$ for all problems.

K-NN Algorithm

Assumption: Similar inputs have similar outputs Denote the set of the k nearest neighbors of $x$ as $S_x$, Then \(dist(x,x′)≥max_{(x′′,y′′)∈S_x}dist(x,x′′)\), We can then define the classifier $h()$ as a function returning the most common label in $S_x$: \(h(x)=mode({y′′:(x′′,y′′)∈S_x})\),

Distance Function

The k-nearest neighbor classifier fundamentally relies on a distance metric. The better that metric reflects label similarity, the better the classified will be. The most common choice is the Minkowski distance: \((∑_{r=1}^d\vert x_r−z_r\rvert^p)^{1/p}.\)

Lower Bound and Upper Bound

We know that the Bayes Risk is lower bound of the risk $R$. And the upperbound is the constant classifier, which essentially predicts always the same constant independent of any feature vectors.

Curse of Dimensionality

The kNN classifier makes the assumption that similar points share similar labels. Unfortunately, in high dimensional spaces, points that are drawn from a probability distribution, tend to never be close together. We can illustrate this on a simple example. We will draw points uniformly at random within the unit cube (illustrated in the figure) and we will investigate how much space the k nearest neighbors of a test point inside this cube will take up.

Let ℓ be the edge length of the smallest hyper-cube that contains all k-nearest neighbor of a test point. Then $ℓ^d≈kn$ and $ℓ≈(\frac{k}{n})^{1/d}$. Now we find that the cubic is exponentially increasing.

Distance to HyperPlane

For machine learning algorithms, this is highly relevant. As we will see later on, many classifiers (e.g. the Perceptron or SVMs) place hyper planes between concentrations of different classes. One consequence of the curse of dimensionality is that most data points tend to be very close to these hyperplanes and it is often possible to perturb input slightly (and often imperceptibly) in order to change a classification outcome. This practice has recently become known as the creation of adversarial samples, whose existents is often falsely attributed to the complexity of neural networks.

Summary of K-NN

- k-NN is a simple and effective classifier if distances reliably reflect a semantically meaningful notion of the dissimilarity. (It becomes truly competitive through metric learning)

- As $n→∞$, $\frac{k}{n}\to 0$ k-NN becomes provably very accurate, but also very slow.

- As d≫0, points drawn from a probability distribution stop being similar to each other, and the kNN assumption breaks down.

Perceptron

Assumption:

- Binary classification (i.e. $y_i∈ { −1,+1 } $)

- Data is linearly separable

Classifier

\(h(x_i)=sign(w^⊤x_i+b)\) $b$ is the bias term (or intercept). Without $b$, the hyperplane will always go through the origin. For writing convience, we will add the bias term to $w$. Then the classifier is $h(x_i)=sign(w^⊤x)$

Update Weight

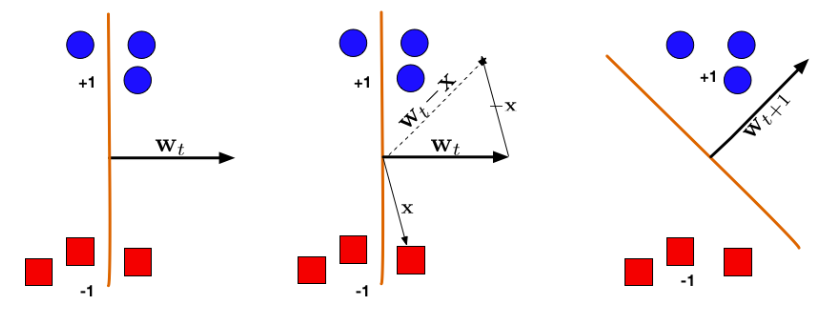

Now that we know what the w is supposed to do (defining a hyperplane the separates the data), let’s look at how we can get such w.

We first initial w with 0. then update the $w$ if misclassify $y_i$: $w ← w + y*x_i$. After going through all points, we train the new weight with all points again until convergence. For geometric explanation, we can see the following figure.

Perceptron Convergence

If a data set is linearly separable, the Perceptron will find a separating hyperplane in a finite number of updates. (If the data is not linearly separable, it will loop forever.)

The argument goes as follows: Suppose $∃w^∗$ such that $y_i(x^⊤w^∗)>0$ $∀(x_i,y_i)∈D$.

Now, suppose that we rescale each data point and the $w^∗$ such that \(\lvert\lvert w^∗\rvert\rvert =1\) and, \(\lvert\lvert x_i\rvert\rvert ≤ 1 ∀ x_i∈D\) Let us define the Margin $γ$ of the hyperplane $w^∗$ as $γ=min_{(x_i,y_i)∈D}|x^⊤_iw^∗|$.

To summarize our setup:

- All inputs xi live within the unit sphere

- There exists a separating hyperplane defined by w∗, with $∥w^*∥=1$ (i.e. $w^∗$ lies exactly on the unit sphere).

- γ is the distance from this hyperplane (blue) to the closest data point.

Then the perceptron algorithm makes at most $\frac{1}{γ^2}$ mistakes. See the proof.

Bayes Classifier

We can estimate the likelihood naively by, \(\hat{P}(x,y)=\frac{∑^n_{i=1}I(x_i=x)I(y_i=y)}{n}.\)

But there is a big problem with this method. The MLE estimate is only good if there are many training vectors with the same identical features as x! In high dimensional spaces (or with continuous x), this never happens!

Naive Bayes

Assumption: $P(x\lvert y)=∏_{α=1}^d P(x_α\rvert y),$

where $x_\alpha$ is the value of feature $\alpha$. In words, feature values are independent given the label! This is a very bold assumption. But sometimes the classifier works well even the assumption is violated.

Until now, the bayes classifier is defined as: \(h(x)=argmax_yP(y|x)=argmax_y∏_{α=1}^dP(x_α|y)P(y)\)

Estimate $P(x_α|y)$

- Categorial features

features: $x_\alpha \in {f_1,…,f_{K_\alpha}}$.

illustration of features: For d dimensional data, there exist d independent dice for each class. Each feature has one die per class. We assume training samples were generated by rolling one die after another. The value in dimension i corresponds to the outcome that was rolled with the ith die.

model: \(P(x_α=j\lvert y=c)=(θ_{jc})_α\) and, \(∑_{j=1}^{K_α}(θ_{jc})_α=1\)

parameter estimation: \((\hat{θ}_{jc})_α=\frac{∑^n_{i=1}I(y_i=c)I(x_{iα}=j)+l}{∑^n_{i=1}I(y_i=c)+lK_α}\), where l is a smoothing parameter. By setting $l=0$ we get an MLE estimator, $l>0$ leads to MAP. If we set $l=+1$ we get Laplace smoothing.

prediction: \(argmax_cP(y=c∣x)∝argmax_c\hat{π}_c∏_{α=1}^d(\hat{θ}_{jc})_α\)

- Multinomial features

features: $x_\alpha \in {0,1,2,3,…,m},\ and\ m=∑_{α=1}^dx_α$.

illustartion of features: There are only as many dice as classes. Each die has d sides. The value of the $i^{th}$ feature shows how many times this particular side was rolled.

model: \(P(x∣m,y=c)=\frac{m!}{x1!⋅x2!...xd!}∏_{α=1}^d(θ_{αc})^{x_α}\)

parameter estimation: \(\hat{θ}_{αc}=\frac{∑^n_{i=1}I(y_i=c)x_{iα}+l}{∑^n_{i=1}I(y_i=c)m_i+l⋅d},\) where $m_i=∑^d_{β=1}x_{iβ}$ denotes the number of words in document i.

prediction: \(argmax_cP(y=c∣x)∝argmax_c\hat{π}_c∏_{α=1}^d(\hat{θ}_{jc})^{x_\alpha}\)

parameter explanation: we have $d$ kinds of document. $θ_{αc}$ means the expected times of word $α$ occurs in the document $d$. $m_i$ is the length of the document $i$. And $x_α$ means how many times word $α$ occurs. Thus the likelihood is the multinomial distribution and the parameter $θ_{αc}$ need estimated. Our final goal is to predict the category of a new document according to the words occurence.

- Continuous features (Gaussian Naive Bayes)

features: $x_\alpha\in R$

illustration of features: Each class conditional feature distribution $P(x_α\lvert y)$ is assumed to originate from an independent Gaussian distribution with its own mean $μ_{α,y}$ and variance $σ^2_{α,y}$.

model: \(P(x_α∣y=c)=N(μ_{αc},σ^2_{αc})\)

parameter estimation: \(\mu_{\alpha c}←\frac{1}{n_c}∑_{i=1}^nI(y_i=c)x_{iα}\\ σ^2_{αc}←\frac{1}{n_c}∑_{i=1}^nI(y_i=c)(x_{iα}−μ_{α_c})^2,\ where\ n_c=∑_{i=1}^nI(y_i=c)\)

Decision Boundary

For binary classification, bayes classifier is not always linear.

- Multinomial features

Let’s go back to the perceptron for binary classification. In perceptron, if we set \(w=log(\theta_{\alpha +})-log(\theta_{\alpha -})\), \(b=log(\pi_+)-log(\pi_-)\). Then we have the bayes classifier is the same as perceptron. Rigorous proof here.

- Continuous features

We will show in the next chapter that it is the same as logistic regression. \(P(y∣x)=\frac{1}{1+e^{−y(w^⊤x+b)}}\)

Note that: In case being confused, the $α$ and $i$ here refers the features, not the sample!!! All these are based on the thereticall model. In real analysis, we just make the iid assumption and product them together for MLE or MAP. In some parts of this post, we will use $x_i$ and $y_i$ to denote the sample when doing estimation. :D

Logsitic Regression

Machine learning algorithms can be (roughly) categorized into two categories:

- Generative algorithms, that estimate $P(x_i,y)$ (often they model $P(x_i\vert y)$ and $P(y)$ separately).

- Discriminative algorithms, that model $P(y\rvert x_i)$

The Naive Bayes is generative. And the logistic regression is discriminative.

Gaussian Naive Bayes Assumption

Suppose $X$ is continuous variable, $P(X_\alpha\lvert Y=c)$ is gaussian distribution $N(\mu_{\alpha c}, \sigma_\alpha)$. And finally the conditional distribution $P(X_\alpha\rvert Y)$ are independent. Y is binary variable.

\(P(Y = 1|X) = \frac{P(Y = 1)P(X|Y = 1)}{P(Y = 1)P(X|Y = 1) +P(Y = 0)P(X|Y = 0)}\) \(P(Y = 1|X) = \frac{1}{1+\frac{P(Y=0)P(X|Y=0)}{P(Y=1)P(X|Y=1)}}\) Note that, \(\frac{P(Y=0)P(X|Y=0)}{P(Y=1)P(X|Y=1)}=exp(log(\frac{1-\pi}{\pi})+\sum_α(\frac{\mu_{\alpha ,-1}-\mu_{\alpha ,1}}{σ^2_α}X_α+\frac{μ^2_{α,1}-μ^2_{α,-1}}{2\sigma^2_α}))\) let \(w_0=-log(\frac{1-\pi}{\pi})-\sum_α\frac{μ^2_{α,1}-μ^2_{α,-1}}{2\sigma^2_α}\), and \(w_α=-\frac{\mu_{\alpha ,-1}-\mu_{\alpha ,1}}{σ^2_α}\) Now we have, \(P(Y = 1|x_i) = \frac{1}{1+exp(-w_0-\sum_{α=1}^dw_αx_α)}=\frac{1}{1+e^{-y(w^Tx_i+b)}}\)

MLE and MAP (Maximum a Posterior)

-

MLE MLE part is quite easy, we just jump to the conclusion: \(argmax_wP(y\lvert w,X)=argmin_w\sum_{i=1}^nlog(1+e^{y_iw^Tx_i})\)

-

MAP We maximize the posterior distribution with prior distribution \(w\sim N(0,σ^2I)\) \(P(w\lvert D)\propto P(Y\rvert X,w)P(w)\) \(\hat{w}_{MAP} =argmax(log(P(Y\rvert X,w)P(w)))= argmin_w\sum_{i=1}^nlog(1+e^{-y_iw^Tx_i})+\frac{1}{2σ^2}w^Tw\)

From the term $w^Tw$, we find that the decision boundary may be quadratic.

This optimization problem has no closed form solution, bu we can use Gradient Descent on the negative log posterior.

This is a confusing part. You should know the difference between MAP and Naive Bayes. MAP give the prior of the parameter $θ$ (also here given the prior of $y$ if we construct the logistic regression from Naive Bayes classifier. But if we just construct the logistic regression directly, we can just ignore the prior distrubution $\pi$ and the estimation of $\hat(μ),\hat{σ^2}$) but Naive Bayes give the prior to the $y$.

Logistic Regression is linear

Consider the condition that holds at the boundary: \(P(Y=1|x,w)=P(Y=−1|x,w)→\frac{1}{1+e^{−w^⊤x}}=\frac{e^{−w^⊤x}}{1+e^{−w^⊤x}}→w^⊤x=0\) So the decision boundary is always linear!

Connection of Naive Bayes and Logistic Regression

| Model | Naive Bayes | Logistic Regression |

|---|---|---|

| Assumption | $P(X\lvert Y)$ is independent | $P(Y\lvert X)$ is simple |

| Likelihood | Joint | Conditional |

| Objective | $∑_ilogP(y_i,x_i)$ | $∑_ilogP(y_i∣x_i)$ |

| Estimation | Closed Form | Iterative (gradient, etc) |

| Decision Boundary | Quadratic/Linear (see below) | Linear |

| When to use | Very little data vs parameters | Enough data vs parameters |

Multinomial Logisitc Regression

Until Now, we just discuss the binary case for logistic regression. Here we make a small extension to the multinomial case. We now have $K$ classes and $K-1$ sets of weights, $w_1,…,w_{K-1}$ \(P(Y=k|x,w)=\frac{e^{w^⊤_kx}}{1+∑^{K−1}_{k′=1}e^{w^⊤_k′x}},\ \ for\ k=1,…,K−1\) and, \(P(Y=K|x,w)=\frac{1}{1+∑^{K−1}_{k′=1}e^{w^⊤_k′x}},\ \ for\ k=1,…,K−1\)

Summary of Logistic Regression and Bayes Classifier

Logistic Regression is the discriminative counterpart to Naive Bayes. In Naive Bayes, we first model $P(x\lvert y)$ for each label y, and then obtain the decision boundary that best discriminates between these two distributions.

In Logistic Regression we do not attempt to model the data distribution $P(x\lvert y)$, instead, we model $P(y\lvert x)$ directly. We assume the same probabilistic form $P(y\rvert x_i)=\frac{1}{1+e^{−y(w^Tx_i+b)}}$, but we do not restrict ourselves in any way by making assumptions about $P(x\vert y)$ (in fact it can be any member of the Exponential Family).

Sorry for this looooog post. I donot want to split the last few parts int two posts since they have strong connection. In the PartII, I will introduce some other methods like SVM. Here is the link for Founadation of Machine Learning Part II.

Reference

- Tom Mitchell “Naive Bayes and Logistic Regression”

- “CIS 520 Machine Learning - UPENN”

- Kilian Weinberger “Machine Learning for Intelligent Systems”